Introduction:

On September 7, 2004, Pakistan lost one of its most cherished literary voices when Ashfaq Ahmed passed away in Lahore at age 79. His death prompted nationwide mourning, with thousands attending funeral prayers and government officials declaring a day of remembrance. Yet two decades later, his words continue to resonate through bookshops in Karachi, university classrooms in Islamabad, and WhatsApp groups across the globe where readers share daily passages from his philosophical masterwork, Zavia.

Ashfaq Ahmed wasn’t just a writer—he was a spiritual guide who made Islamic mysticism accessible to everyday people, a television pioneer who transformed Pakistani broadcasting, and half of the country’s most influential literary partnership alongside his wife, novelist Bano Qudsia.

Early Life: From Firozpur to Partition

Born on August 22, 1925, in Firozpur, Punjab (then British India, now part of Indian Punjab), Ashfaq Ahmed grew up during the turbulent final decades of colonial rule. His family belonged to the Muslim middle class, where education was valued despite limited financial resources. His father worked in government service, ensuring young Ashfaq received quality schooling even as political tensions mounted around them.

The Partition of India in 1947 profoundly shaped Ashfaq Ahmed’s worldview. Like millions of Muslims, his family migrated to the newly-formed Pakistan, leaving behind ancestral homes and severed family connections. This traumatic displacement—witnessing communal violence and the collapse of centuries-old communities—instilled in him a lifelong commitment to spiritual values that transcended political boundaries. The themes of belonging, identity, and inner anchoring that would define his later work all trace back to this formative experience.

Education and Intellectual Formation

Ashfaq Ahmed completed his higher education at Government College Lahore, one of South Asia’s most prestigious institutions. During the late 1940s, the college campus buzzed with intellectual ferment as students debated the future of their new nation. Here, Ahmed was exposed to both Western philosophy and Eastern spiritual traditions, studying alongside future luminaries of Pakistani literature.

His education went beyond formal classrooms. Ashfaq Ahmed immersed himself in classical Urdu poetry—devouring the works of Ghalib, Iqbal, and Rumi—while also exploring Islamic mysticism and Sufi traditions. This dual engagement with literary craft and spiritual inquiry would become his signature strength: the ability to embed profound philosophical insights within accessible, beautiful prose.

It was at Government College that Ashfaq Ahmed met a fellow literature enthusiast who would change his life forever.

The Love Story: Meeting Bano Qudsia

Among the college’s literary society members was Bano Qudsia, a brilliant young woman equally passionate about Urdu literature and philosophical questions. Their relationship blossomed through shared discussions of Sufism, poetry, and existential mysteries—intellectual companionship that gradually deepened into love.

In 1951, Ashfaq Ahmed and Bano Qudsia married, beginning a 53-year partnership that would produce some of Urdu literature’s finest works. Unlike typical marriages of their era, theirs was a true intellectual collaboration. They regularly critiqued each other’s manuscripts, shared spiritual practices, and hosted joint literary gatherings at their modest Lahore home.

Bano Qudsia achieved literary greatness in her own right—her novel “Raja Gidh” is considered among Urdu’s greatest—but the couple’s complementary styles enriched both their bodies of work. Ashfaq’s writing leaned contemplative and dialogue-driven, while Bano’s explored psychological complexity through intricate narratives. Together, they created a comprehensive vision of spiritual literature that influenced generations.

Their Lahore residence became an informal salon where Pakistan’s literary and intellectual elite gathered for mehfils (literary gatherings), discussing everything from classical poetry to contemporary social issues. This couple demonstrated that marriage could be a partnership of equals pursuing shared creative and spiritual goals.

Literary Career: Finding His Voice

Ashfaq Ahmed began writing seriously in the early 1950s, contributing short stories to Urdu literary magazines like Adab-e-Latif and Funoon. His early fiction explored the psychological dimensions of ordinary people facing moral dilemmas, always with an underlying spiritual dimension.

What distinguished Ashfaq Ahmed’s prose was its accessibility. Unlike writers who favored ornate, classical poetic language, he wrote in simple, conversational Urdu that educated readers and common people alike could understand. Yet this simplicity masked profound depth—his stories addressed universal human questions about meaning, purpose, and transcendence.

His writing style featured heavy dialogue, minimal description, and a focus on internal transformation rather than external action. Characters in Ashfaq Ahmed’s stories often underwent spiritual awakenings, recognizing that material success couldn’t satisfy deeper hungers. This theme reflected his own Sufi-influenced worldview: that life’s purpose centered on purifying the self (tazkiya) and developing direct connection with the Divine.

Zavia: The Philosophy That Defined a Generation

In 1963, Ashfaq Ahmed published the first volume of Zavia (meaning “angle” or “perspective”), a collection of philosophical essays that would become his most enduring contribution to Urdu literature. Over the following four decades until his death, he would release multiple Zavia volumes, each containing short contemplative pieces addressing life’s fundamental questions.

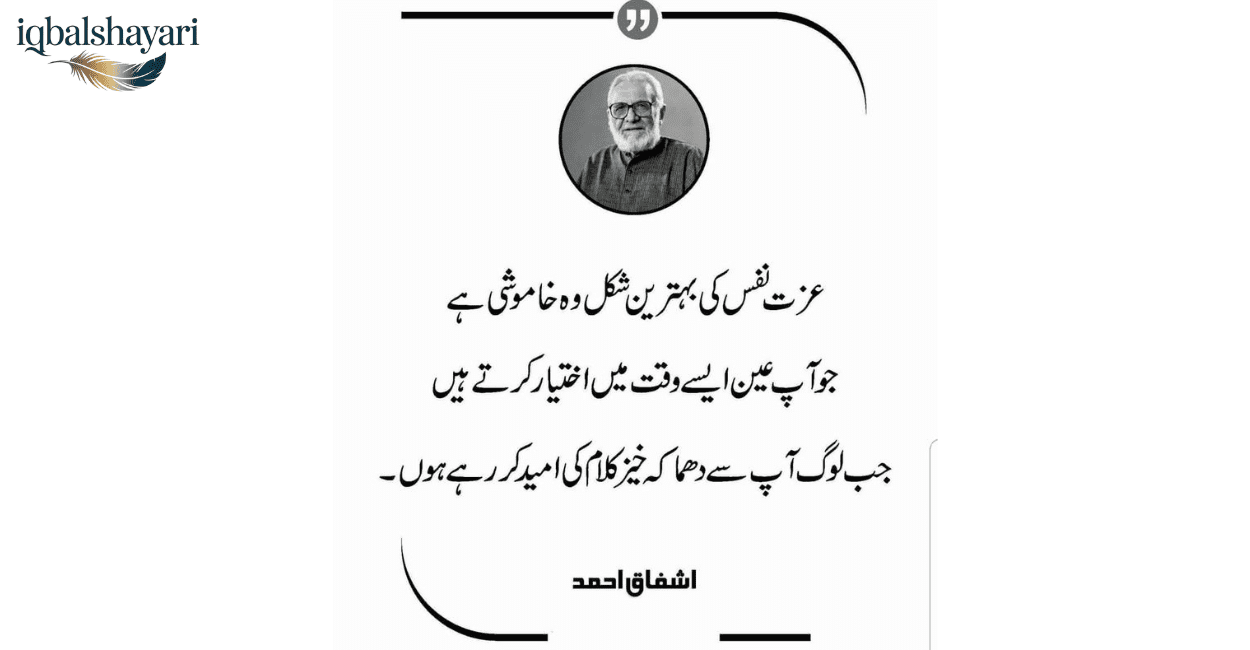

Zavia’s genius lay in its format and approach. Each essay ran just one to three pages, making it perfect for busy readers seeking spiritual nourishment without committing to lengthy texts. Ashfaq Ahmed tackled topics like the difference between knowledge and wisdom, the purpose of suffering, detachment from materialism, and achieving inner peace—all through a Sufi lens but without requiring readers to possess religious scholarship.

The philosophy running through Zavia emphasized several core principles:

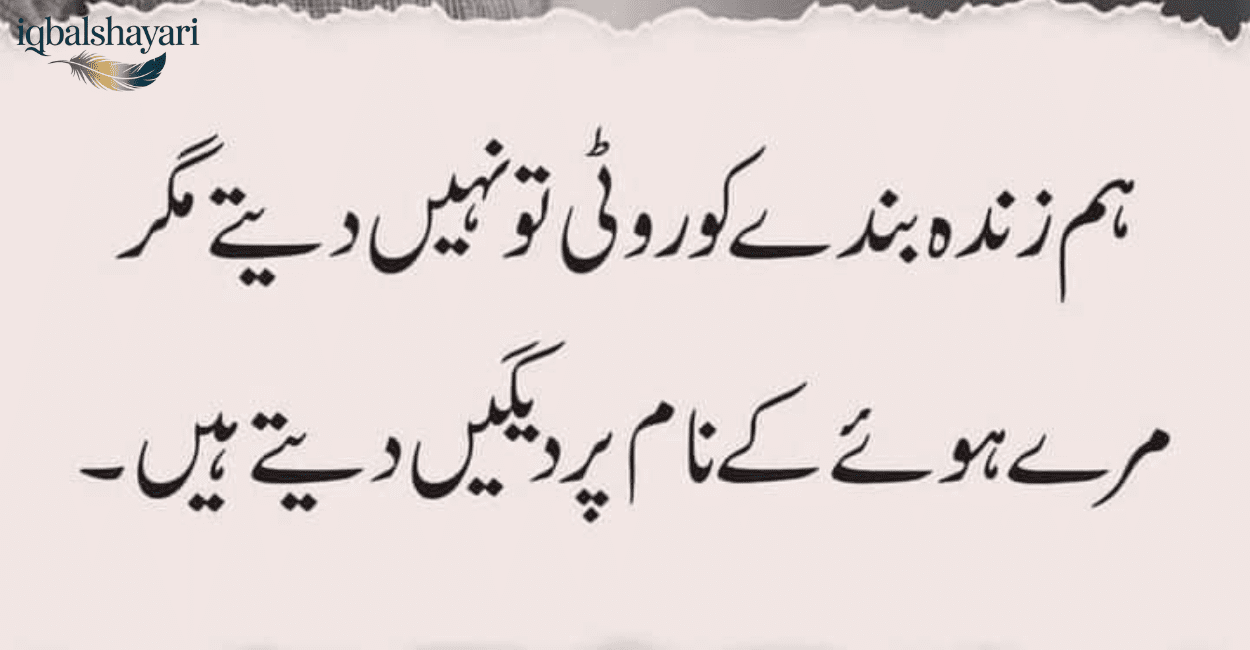

Spiritual over material fulfillment: Ashfaq Ahmed consistently argued that true contentment (qana’at) came from inner development, not external achievements. Wealth and status were acceptable tools but dangerous goals.

Wisdom versus knowledge: He distinguished between ilm (information gathering) and hikmat (practical understanding). A person could possess multiple degrees yet lack the wisdom to live well.

Self-purification as life’s purpose: Drawing from Islamic mysticism, Ashfaq Ahmed presented self-improvement and ego-dissolution (fana) as humanity’s primary work.

Love as transformative force: Spiritual love (ishq) served as a bridge between human and Divine, capable of fundamentally reshaping one’s character.

Today, Zavia remains a bestseller across Pakistan and among Urdu-speaking communities in India, the UK, and North America. University students in Lahore and Karachi buy worn copies from Urdu Bazaar bookshops, young professionals share passages in WhatsApp groups, and spiritual seekers find in Ashfaq Ahmed’s words the guidance their modern lives desperately need.

Television Pioneer: Baithak and Broadcasting Revolution

While Ashfaq Ahmed’s books reached educated readers, his television work brought his voice into millions of homes across Pakistan. In the 1970s, he began hosting Baithak (meaning “sitting room”) on Pakistan Television (PTV), a talk show that would run for over two decades and become a cultural institution.

Baithak’s format was revolutionary in its simplicity. The set resembled a traditional Pakistani sitting room—minimal, unpretentious. Ashfaq Ahmed sat conversing with guests in an intimate, unhurried manner that prioritized listening over performance. Guests ranged from famous writers and artists to unknown individuals with compelling life stories.

Unlike entertainment-focused programming, Baithak offered substantive intellectual and spiritual discussions accessible to all education levels. Families gathered to watch episodes together, and conversations from the show continued in homes, colleges, and workplaces for days afterward. The program demonstrated television’s potential as an educational medium, not merely an entertainment device.

Beyond Baithak, Ashfaq Ahmed wrote numerous television dramas for PTV, including “Uchhay Burj Lahore Day” (exploring Lahore’s cultural heritage) and adaptations of his short stories. His dramatic work maintained his literary characteristics: dialogue-intensive, character-driven, morally resonant without preaching, and realistic in depicting middle-class Pakistani life.

He also contributed to Radio Pakistan before television’s rise, hosting literary programs and spiritual talks that reached audiences across the country.

Major Literary Works

Beyond Zavia, Ashfaq Ahmed produced an impressive body of work spanning multiple genres:

Novels: “Talash” (The Search) followed a protagonist’s journey from material success to spiritual fulfillment, critiquing modern consumerism. “Godaan” explored themes of sacrifice and devotion in rural settings, integrating folk wisdom with spiritual insight.

Short story collections: “Teesra Kinara” (The Third Shore) and “Aik Mohabbat Sau Afsane” (One Love, Hundred Stories) demonstrated his narrative range, featuring diverse voices and unexpected plot developments while maintaining philosophical undertones.

Plays and dramas: His theatrical works adapted Sufi parables and folk tales for contemporary audiences, always finding modern relevance in traditional wisdom.

Essays: Hundreds of pieces appeared in literary magazines covering social, political, and spiritual topics, establishing Ashfaq Ahmed as a leading public intellectual in post-independence Pakistan.

Awards and National Recognition

Ashfaq Ahmed’s contributions earned Pakistan’s highest civilian honors. In 1983, he received the Pride of Performance, the nation’s premier literary award. The Sitara-e-Imtiaz (Star of Excellence) followed in 1987, recognizing his cultural impact. Two years before his death, the government awarded him the Hilal-e-Imtiaz (Crescent of Excellence) in 2002, Pakistan’s second-highest civilian honor.

These awards placed Ashfaq Ahmed among the nation’s most decorated cultural figures, alongside poets like Faiz Ahmed Faiz and national icons like Allama Iqbal. Universities granted him honorary doctorates, literary organizations established awards in his name, and the Pakistan Academy of Letters recognized him as a defining voice of Urdu prose in the twentieth century.

Personal Character and Daily Life

Despite fame and national honors, Ashfaq Ahmed maintained remarkable humility. He dressed simply in traditional shalwar kameez, avoided celebrity culture, and lived modestly in his Lahore home. Contemporaries remember him as genuinely interested in others—whether speaking with famous writers or unknown visitors seeking guidance, he gave complete attention.

His daily routine reflected his spiritual commitments: early morning prayer and meditation, extended writing sessions, regular spiritual practices, and evening gatherings with literary friends. He mentored young writers without expectation, often providing anonymous financial support to struggling artists.

Ashfaq Ahmed maintained distance from partisan politics, believing spiritual awakening and individual transformation mattered more than political movements. This apolitical stance made his work accessible across Pakistan’s political divides—readers from all backgrounds found wisdom in his pages.

Death and Enduring Legacy

When Ashfaq Ahmed died on September 7, 2004, in Lahore after a period of declining health, the outpouring of grief reflected his profound impact. Government officials attended funeral prayers, PTV broadcast special tributes, newspapers dedicated entire sections to his memory, and literary organizations organized memorial gatherings across Pakistan.

Bano Qudsia, his wife and literary partner of 53 years, continued promoting his legacy until her own death in 2017. Together they had shaped Pakistani literature through decades of creative work and intellectual partnership.

Twenty years after his passing, Ashfaq Ahmed’s influence remains vibrant. His books consistently rank among bestsellers in Pakistan. Students study his work in university Urdu departments from Lahore to Karachi. YouTube channels archive Baithak episodes, introducing new generations to his conversational wisdom. Social media pages share daily Zavia passages, and reading groups meet in cities worldwide to discuss his philosophy.

His legacy extends beyond literary circles. Young professionals facing career pressure find guidance in Zavia’s teachings about material versus spiritual success. Spiritual seekers discover accessible mysticism in his Sufi-influenced wisdom. Couples reference his marriage to Bano Qudsia as an example of intellectual partnership. And anyone struggling with modern life’s complexities can turn to Ashfaq Ahmed’s words for timeless insight.

Where to Access His Works Today

For readers in Pakistan, Ashfaq Ahmed’s books are widely available. Major publishers like Sang-e-Meel Publications and Maktaba-e-Daniyal in Lahore maintain his complete works. Bookstores in Urdu Bazaar (Lahore and Karachi), Anarkali Bazaar (Lahore), and shopping districts in Islamabad stock his titles, with prices ranging from PKR 200-800 per book depending on edition quality.

In India, Urdu bookstores in Delhi’s Urdu Bazaar, Mumbai’s Mohammed Ali Road area, and Hyderabad’s Charminar district carry his works, though availability can be limited. Online platforms like Rekhta.org provide digital access to much of his writing, serving readers worldwide.

Diaspora communities in the UK, USA, and Canada can find his books through specialized Urdu literature retailers or order online, though shipping costs and limited availability remain challenges. E-books and PDF versions circulate online, though readers should seek legitimate sources to support publishers and authors’ estates.

For those new to Ashfaq Ahmed, start with any Zavia volume—the short essays allow easy entry into his philosophical world. Follow with his novel “Talash” for narrative experience, then explore his short story collections. Baithak episodes available on YouTube provide additional context and showcase his conversational brilliance.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Ashfaq Ahmed most famous for?

Ashfaq Ahmed is most famous for Zavia, his multi-volume collection of philosophical essays offering spiritual wisdom through accessible Urdu prose, and Baithak, his groundbreaking television talk show on PTV that ran for over two decades. He’s also celebrated for his marriage to fellow writer Bano Qudsia and receiving Pakistan’s highest civilian awards.

When and where was Ashfaq Ahmed born?

Ashfaq Ahmed was born on August 22, 1925, in Firozpur, Punjab, which was then part of British India and is now located in Indian Punjab. His family migrated to Pakistan during the 1947 Partition.

How did Ashfaq Ahmed and Bano Qudsia meet?

Ashfaq Ahmed and Bano Qudsia met as students at Government College Lahore in the late 1940s. Both participated in the college’s literary societies and bonded over shared interests in Urdu literature, philosophy, and Sufism. They married in 1951 and remained partners for 53 years until Ashfaq’s death.

What does Zavia mean and what is it about?

Zavia means “angle” or “perspective” in Urdu. It’s Ashfaq Ahmed’s collection of short philosophical essays addressing life’s fundamental questions through a Sufi-influenced spiritual lens. Topics include the difference between knowledge and wisdom, material versus spiritual fulfillment, finding inner peace, and understanding suffering’s purpose—all written in simple, accessible language.

What awards did Ashfaq Ahmed receive?

Ashfaq Ahmed received Pakistan’s three highest civilian honors: the Pride of Performance (1983) for literary contributions, Sitara-e-Imtiaz (1987) as the third-highest civilian award, and Hilal-e-Imtiaz (2002), the second-highest honor, recognizing his lifetime cultural achievements.

What was Ashfaq Ahmed’s writing style?

Ashfaq Ahmed wrote in simple, conversational Urdu avoiding ornate classical poetic language. His style featured heavy dialogue, minimal description, character-driven narratives focused on internal transformation, and integration of Sufi parables and Islamic references. He made complex mystical concepts understandable to readers of all educational backgrounds.

Where can I buy Ashfaq Ahmed’s books?

In Pakistan, find his books at major bookstores in Lahore (Urdu Bazaar, Anarkali Bazaar), Karachi (Urdu Bazaar, Saddar area), and Islamabad (Jinnah Super area). Publishers like Sang-e-Meel and Maktaba-e-Daniyal sell directly. In India, check Urdu bookstores in Delhi, Mumbai, and Hyderabad. Internationally, Rekhta.org offers digital access, and specialized online retailers serve diaspora communities.

Is Ashfaq Ahmed still relevant today?

Yes, Ashfaq Ahmed remains highly relevant. His Zavia philosophy addresses timeless human struggles—finding meaning, balancing material and spiritual life, maintaining inner peace amid chaos—that resonate with contemporary readers facing career pressure, social media comparison, and identity crises. His accessible approach to Islamic mysticism provides practical spiritual guidance for modern challenges.

Conclusion

Ashfaq Ahmed’s life story—from his 1925 birth in pre-Partition Firozpur through his seven-decade career until his 2004 death in Lahore—represents a remarkable synthesis of literary excellence, spiritual depth, and cultural influence. He transformed Pakistani television through Baithak, elevated Urdu prose through his novels and essays, and made Sufi philosophy accessible to millions through Zavia.

His marriage to Bano Qudsia demonstrated that intellectual partnership between equals could produce extraordinary creative work. His receipt of Pakistan’s highest honors—Pride of Performance, Sitara-e-Imtiaz, and Hilal-e-Imtiaz—confirmed his status as a national cultural treasure.

Twenty years after his passing, Ashfaq Ahmed’s words continue guiding readers through life’s complexities. Students in Lahore universities analyze his literary techniques, spiritual seekers find wisdom in Zavia’s pages, and anyone questioning material culture’s sufficiency discovers in his work an invitation inward—toward the self-knowledge that, in his view, represents life’s ultimate purpose.

For those seeking meaning beyond materialism, wisdom beyond information, and peace beyond comfort, Ashfaq Ahmed’s biography and works offer a tested path rooted in centuries of spiritual tradition yet remarkably applicable to modern challenges. His legacy lives not just in libraries and academic studies, but in the daily lives of readers.