Introduction: Who Transformed American Culture

When Andy Warhol unveiled his Campbell’s Soup Cans at a Los Angeles gallery in 1962, critics didn’t know whether to celebrate or dismiss it. Some called it genius. Others called it a joke. But Warhol had done something no artist had attempted before—he transformed everyday grocery store products into fine art, forever changing how we think about creativity, fame, and American consumer culture.

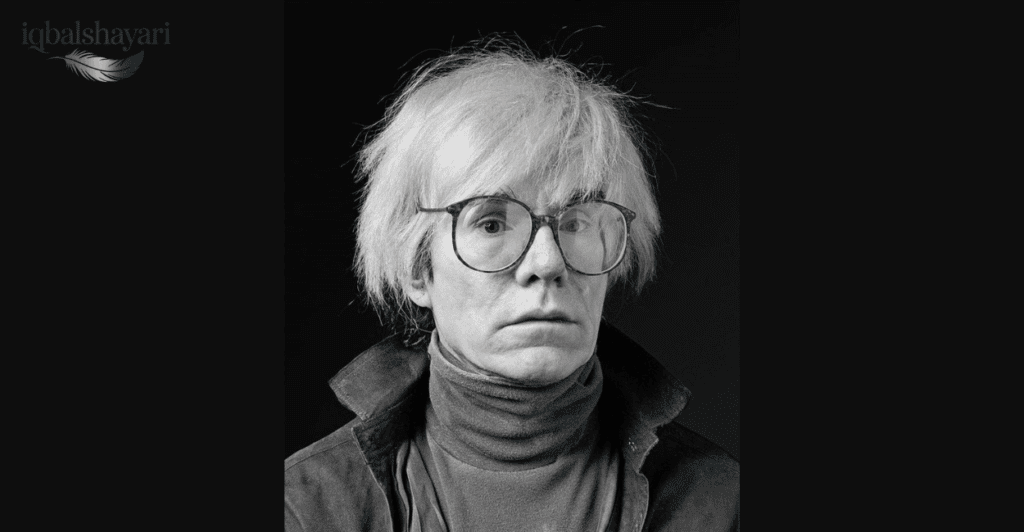

Born Andrew Warhola on August 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Warhol grew up in a working-class Ruthenian Catholic family. His father worked construction while his mother, Julia, created folk art that would later influence her son’s creative vision. Young Andy suffered from Sydenham’s chorea as a child, spending long periods bedridden where he drew, collected celebrity photographs, and developed an obsession with Hollywood glamour that would define his career.

After graduating from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in 1949 with a degree in pictorial design, Warhol moved to New York City and quickly became one of the most successful commercial illustrators of the 1950s. He created advertisements for major magazines like Glamour, Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar, developing his distinctive blotted-line drawing technique and earning substantial income that allowed him to collect art and transition into fine art production.

The Birth of Pop Art and Warhol’s Revolution

Pop Art emerged in the late 1950s as a reaction against Abstract Expressionism’s emotional intensity and intellectual pretensions. While British artists like Richard Hamilton pioneered the movement in the UK, American Pop Art developed independently with artists including Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Claes Oldenburg.

Warhol’s breakthrough came in 1962 with two revolutionary series that scandalized the art world. His Campbell’s Soup Cans—32 canvases depicting each soup variety then available—challenged every assumption about what qualified as art. Why paint soup cans? Warhol explained simply: “I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again.”

But the Campbell’s Soup series was more than personal preference. It represented Warhol’s radical idea that art shouldn’t be precious, unique, or handcrafted. By choosing mass-produced commercial products as subjects and employing mechanical reproduction techniques, he eliminated the artist’s emotional “hand” and questioned fundamental assumptions about artistic originality and authorship.

His Marilyn Diptych, created shortly after Marilyn Monroe’s death in August 1962, cemented his signature style. The work featured 50 repeated images of the actress derived from a publicity photograph, with vibrant color panels contrasting against fading black-and-white images—a meditation on fame, mortality, and how media saturates and depletes meaning through endless repetition.

The Factory: Where Art Became Industry

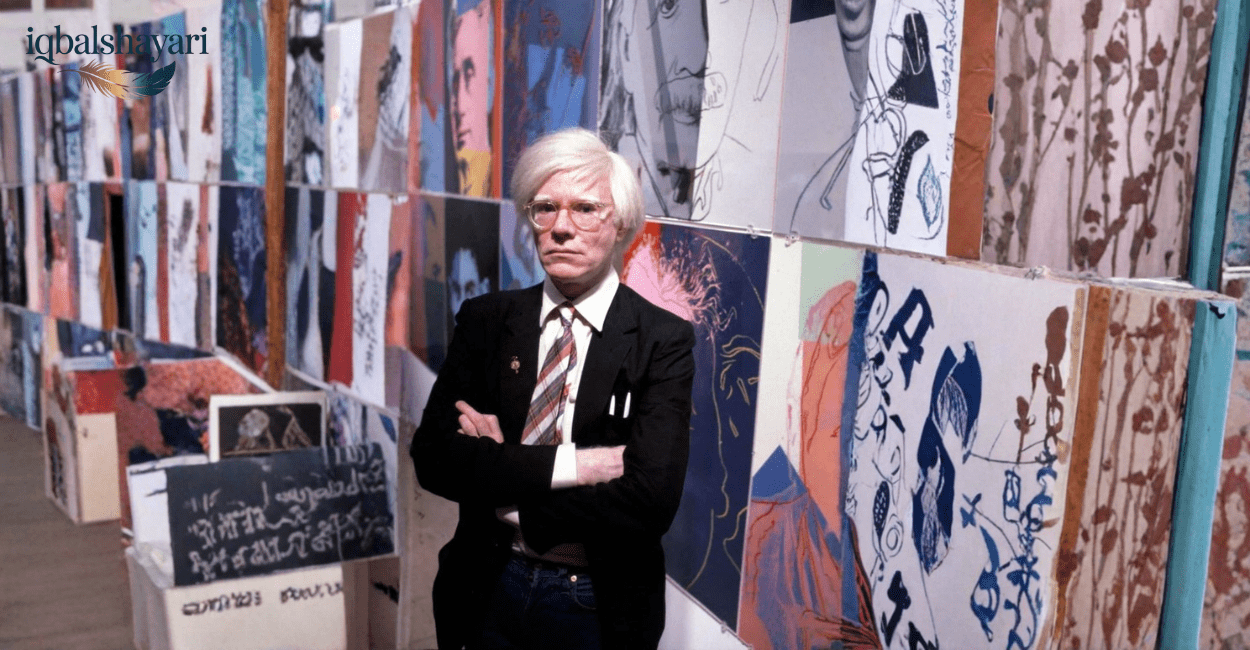

In 1963, Warhol moved his studio to a former hat factory at 231 East 47th Street in Manhattan. Decorator Billy Name covered the entire space in silver paint and aluminum foil, creating the legendary Factory—part art studio, part film production center, part 24-hour party venue, and entirely unlike any artist workspace before it.

The Factory operated on an open-door policy, attracting an eclectic mix of artists, musicians, celebrities, socialites, drag queens, and outsiders. Factory Superstars like Edie Sedgwick, Candy Darling, Ultra Violet, and poet Gerard Malanga became Warhol’s muses, assistants, and film subjects. Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground rehearsed there while Warhol designed their iconic banana album cover.

This collaborative production model challenged traditional notions of artistic genius. Warhol employed assistants to prepare screens, mix paints, and pull prints while he directed the overall creative vision. When asked if his assistants actually made his art, Warhol responded, “I think somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me.” This wasn’t laziness—it was a deliberate statement about mass production, authorship, and the artist-as-director rather than craftsman.

The Factory era ended abruptly on June 3, 1968, when radical feminist Valerie Solanas shot and nearly killed Warhol. The attack severely affected his health—he wore a surgical corset for the rest of his life—and transformed The Factory from an open creative laboratory into a more secure, professional business operation.

Warhol’s Artistic Techniques and Methods

Warhol’s primary technique was silkscreen printing (also called serigraphy), a commercial reproduction method he adopted in 1962. The process involved selecting photographic source images from magazines or newspapers, converting them to high-contrast acetate positives, exposing them onto photo-sensitive mesh screens, and pushing acrylic or oil-based ink through the resulting stencil onto canvas.

This mechanical approach served multiple purposes. It mimicked industrial mass production, allowing creation of multiple versions and variations. It removed visible brushwork and artistic “hand,” emphasizing concept over craft. And it perfectly embodied Warhol’s themes about consumer culture, celebrity, and image reproduction in modern media.

His color choices were equally revolutionary. Rather than naturalistic hues, Warhol employed bright, non-naturalistic commercial color schemes—electric blue faces, fluorescent orange backgrounds, hot pink lips. He assigned colors arbitrarily, creating multiple variations of the same image in different palettes, turning art into collectible series like baseball cards or product lines.

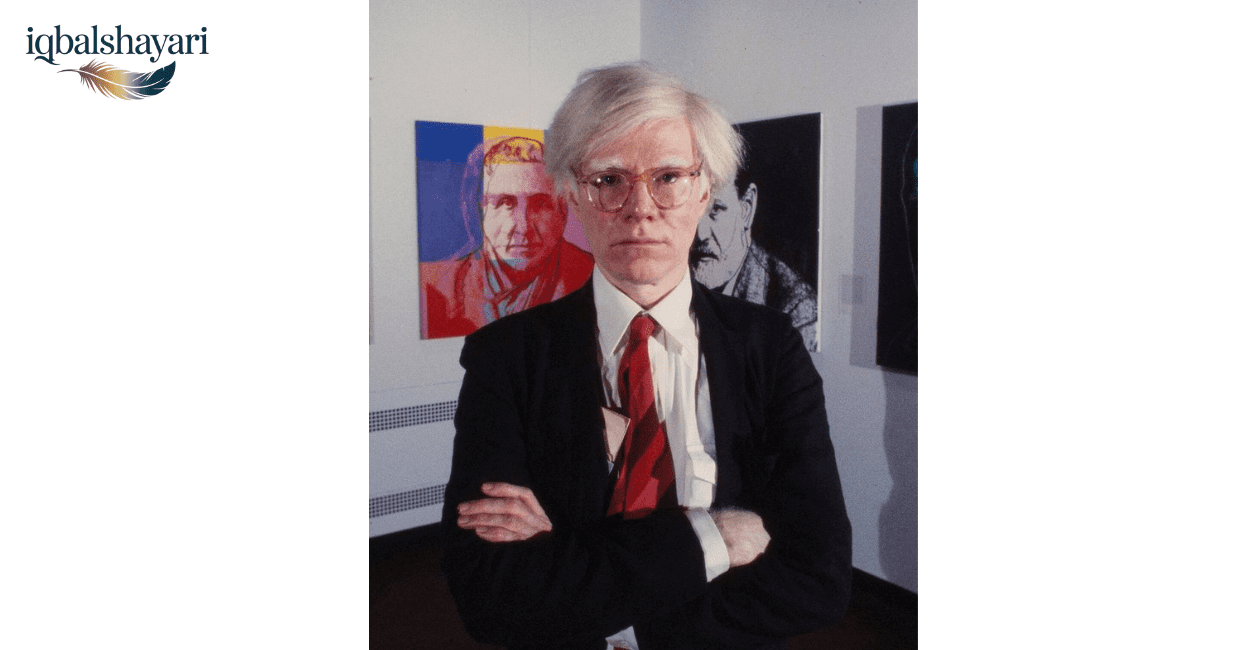

From the 1970s onward, Warhol used a Polaroid Big Shot camera to create source images for commissioned portraits. He’d photograph subjects against plain backdrops, select the best shots, project them onto prepared canvases, apply acrylic paint in flat color zones, and add final silkscreen layers for photographic detail. This assembly-line portrait process generated substantial income while maintaining his artistic relevance.

Major Works and Iconic Series

Beyond Campbell’s Soup and Marilyn, Warhol created several defining bodies of work. His Disaster Series (1963-1964) depicted car crashes, electric chairs, suicides, and race riots using newspaper photographs. Works like “Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster)” demonstrated Warhol’s darker social commentary on how media repetition desensitizes us to violence and death.

The Flowers series (1964-1965), based on a photograph from Modern Photography magazine, became hugely popular and commercially successful. These bright, decorative works showed Warhol’s range beyond celebrity and disaster themes.

His Brillo Boxes (1964)—plywood sculptures covered with silkscreened reproductions of Brillo soap pad packaging—raised philosophical questions about art objects. If a Brillo Box in a supermarket costs pennies but an identical-looking Warhol Brillo Box in a gallery costs thousands, what creates artistic value? The object itself or the institutional context?

Warhol’s Mao series (1972-1973), created after President Nixon’s visit to China, explored political iconography and the mass production of leader imagery. Later, he created hundreds of commissioned Polaroid-based portraits of celebrities and wealthy patrons including Muhammad Ali, Elizabeth Taylor, Michael Jackson, and Mick Jagger, combining artistic practice with commercial enterprise.

Where to See Warhol’s Art Across America

The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh houses the world’s most comprehensive collection with over 900 paintings, 2,000 drawings, 1,000 prints, and 4,000 photographs. Located at 117 Sandusky Street, the seven-story museum offers the deepest dive into Warhol’s complete body of work. Adult admission is $20, with free entry on first Fridays from 5-10 PM.

In New York City, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) displays the complete 32-canvas Campbell’s Soup Cans series along with Gold Marilyn Monroe. The Whitney Museum of American Art features significant holdings including disaster series paintings, while The Met maintains rotating Warhol exhibitions.

The Art Institute of Chicago holds major Warhol pieces, as does the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) on the West Coast. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC also maintain important collections.

For those planning museum visits, the Pittsburgh Warhol Museum requires 2-3 hours for a thorough experience. In NYC, combining MoMA and the Whitney in one day offers comprehensive Warhol exposure. Most museums allow photography without flash, making them ideal for art students and enthusiasts documenting their visits.

Understanding Warhol’s Art Market and Values

Andy Warhol remains one of the most traded artists at auction, with works ranging from affordable prints to record-breaking paintings. In May 2022, Shot Sage Blue Marilyn sold for $195 million at Christie’s, setting the record for the most expensive 20th-century artwork ever sold at auction.

Standard edition prints from popular series like Flowers, Marilyn, or Campbell’s Soup typically range from $5,000 to $50,000 depending on edition size, condition, and provenance. Unique prints and trial proofs command $50,000 to $500,000. Polaroid photographs from Warhol’s portrait sessions sell for $10,000 to $100,000.

Paintings occupy a different stratosphere. Minor works start around $500,000, while major paintings from iconic series range from $5 million to $50 million or more. Museum-quality masterworks from the early 1960s Pop Art period can exceed $100 million.

Authentication presents the biggest challenge for collectors. The Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board operated from 1996 to 2011 but disbanded due to litigation costs, leaving no official authentication body today. This creates significant risk in the market, as numerous fakes and misattributed works circulate.

When considering Warhol purchases, work only with reputable dealers who provide comprehensive provenance documentation, exhibition history, and literature references. Request technical analysis of materials and techniques. Be wary of suspiciously low prices—if a Marilyn print seems too cheap, it probably is. Major auction houses like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips offer more security than unknown dealers, while established galleries like Gagosian and Pace specialize in authenticated works.

Warhol’s Multimedia Empire

Warhol’s creativity extended far beyond painting and printmaking. Between 1963 and 1968, he produced over 60 films that challenged conventional narrative and cinematic technique. Sleep (1963) showed poet John Giorno sleeping for over five hours. Empire (1964) presented an eight-hour static shot of the Empire State Building. Chelsea Girls (1966) became the first commercially successful underground film, using dual-screen projection.

His management of The Velvet Underground bridged visual art and rock music. Warhol designed their famous banana album cover, organized multimedia “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” performances combining music, film, and light shows, and produced albums for singer Nico.

In 1969, Warhol founded Interview magazine, which pioneered celebrity-focused journalism through lengthy, minimally-edited conversations. The publication became a platform for emerging talents and another vehicle for Warhol’s brand extension.

His later television work included Andy Warhol’s TV (1980-1983) on cable access and Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes (1985-1987) on MTV, continuing his documentation of contemporary culture until his death.

Why Warhol Still Matters in 2026

Warhol’s influence permeates contemporary culture in ways that would have delighted him. His famous prediction that “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” perfectly anticipated Instagram influencers, viral videos, and social media celebrity culture. The Factory Superstar model prefigured reality TV and YouTube personalities.

His understanding of image reproduction and mass media proved remarkably prescient. Selfie culture mirrors Warhol’s obsessive self-portraiture. Meme culture employs Warholian repetition and variation. NFTs and digital art echo his concepts about editions, reproduction, and the nature of artistic originals.

Contemporary artists from Jeff Koons to Takashi Murakami to KAWS directly descend from Warhol’s fusion of high art and commercial culture. His Factory production model—employing assistants and treating art as collaborative business—became standard practice for successful contemporary artists operating at scale.

Fashion continues embracing Warhol through collaborations with brands like Supreme, Comme des Garçons, and Calvin Klein. His screen-printed aesthetic influenced graphic design, album covers, and visual communication across industries.

Warhol died on February 22, 1987, at age 58 from cardiac complications following gallbladder surgery. His will established the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, which supports contemporary artists and has granted over $250 million since its inception.

Warhol’s Cultural Impact Beyond Art

Warhol’s legacy extends into business, philosophy, and cultural criticism. He pioneered the artist-as-brand concept, treating creative practice as entrepreneurial enterprise decades before it became common. His commissioned portrait business generated income while maintaining artistic relevance—a balance many contemporary artists still struggle to achieve.

His commentary on consumer culture and celebrity remains urgently relevant. Warhol understood that in media-saturated societies, image often matters more than substance, repetition creates meaning, and fame itself becomes a commodity separate from achievement or talent.

The LGBTQ+ community recognizes Warhol as an important though complicated figure. While he never publicly declared his sexuality during his lifetime, The Factory provided space for transgender pioneers like Candy Darling and challenged conventional gender and social norms.

His Time Capsules—610 sealed boxes containing personal effects, mail, newspapers, and gifts accumulated monthly from 1974 to 1987—offer unprecedented documentation of daily life, creative process, and cultural production. Now housed at The Andy Warhol Museum, these capsules continue yielding research insights.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Andy Warhol most famous for?

Andy Warhol is most famous for pioneering Pop Art through iconic works like Campbell’s Soup Cans and Marilyn Monroe portraits. He revolutionized art by elevating commercial imagery and consumer products to fine art status while employing mass-production silkscreen printing techniques. His Factory studio became legendary as the epicenter of 1960s avant-garde culture, and his “15 minutes of fame” quote perfectly predicted modern celebrity culture.

Why did Andy Warhol paint Campbell’s Soup Cans?

Warhol painted Campbell’s Soup Cans because he ate the soup daily for lunch and wanted to depict something universally recognizable in American culture. The mundane subject challenged traditional art definitions while commenting on mass production and consumer culture. He appreciated the packaging’s visual uniformity and transformed ordinary commercial products into subjects worthy of serious artistic contemplation.

How much is Andy Warhol’s art worth today?

Warhol’s art values range dramatically from $5,000 for standard edition prints to over $195 million for museum-quality paintings. His Shot Sage Blue Marilyn sold for $195 million in 2022, setting a record for 20th-century art. Mid-range paintings typically sell between $5 million and $50 million, while Polaroid photographs command $10,000 to $100,000. Signed prints from popular series like Flowers or Marilyn typically range $15,000 to $50,000.

Where can I see Andy Warhol’s artwork in America?

The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania houses the world’s largest collection with over 900 paintings. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York displays the complete Campbell’s Soup Cans series. Other major holdings exist at the Whitney Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Most major American art museums feature at least some Warhol works.

What technique did Andy Warhol use to create his art?

Warhol primarily used silkscreen printing (serigraphy), a commercial reproduction technique involving photo-based stencils on mesh screens. He selected photographic source images, transferred them to acetate positives, exposed photo-sensitive screens, and pushed acrylic or oil-based inks through the stencil onto canvas. This mechanical process allowed mass production, eliminated visible brushwork, and perfectly suited his themes of consumer culture and image reproduction.

Did Andy Warhol actually create his own art?

Yes, though Warhol employed assistants extensively at The Factory. He conceptualized works, selected subjects, made creative decisions, and often participated in production, but assistants frequently executed technical aspects like screen preparation and printing. This collaborative model intentionally challenged traditional notions of artistic authorship and individual creative genius. Warhol saw himself as director rather than sole creator, embracing factory-style production as an artistic statement.

How do I know if an Andy Warhol artwork is authentic?

Authentic Warhol works require comprehensive provenance documentation, exhibition history, and literature references. Since the Authentication Board dissolved in 2011, work with reputable dealers who provide detailed documentation and written guarantees. Red flags include suspiciously low prices, lack of provenance, materials inconsistent with Warhol’s known practices, and sellers unwilling to guarantee authenticity in writing. Consider professional appraisal and technical analysis for purchases over $10,000.

What was Andy Warhol’s Factory?

The Factory was Warhol’s Manhattan studio complex (1963-1987) functioning as art production facility, film studio, party venue, and social laboratory. The original silver-foil-covered space at 231 East 47th Street attracted artists, celebrities, musicians, and socialites in a 24-hour creative scene. Factory assistants produced artworks while Warhol filmed visitors and hosted legendary parties. After he was shot in 1968, later Factory locations became more professional operations focusing on commissioned work.

Conclusion

Andy Warhol transformed not just how we create art, but how we understand fame, commerce, identity, and image in contemporary culture. His pioneering fusion of art and business, high and low culture, continues influencing creative practice across disciplines decades after his death in 1987.

Whether you’re an art student studying his revolutionary silkscreen technique, a collector assessing investment opportunities, a tourist planning museum visits, or simply curious about why soup cans became art, Warhol’s legacy offers endless insights. His work proves that art doesn’t require precious materials or rarified subjects—it requires vision, courage, and willingness to challenge assumptions about what deserves our attention.

Visit The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh for the most comprehensive experience, explore his Campbell’s Soup Cans at MoMA in New York, or discover Warhol holdings at museums nationwide. His art remains powerfully present, reminding us that the ordinary can become extraordinary when viewed through creative eyes—and that everyone, as he predicted, really can be famous for 15 minutes in our media-saturated world.

Read more: Mawlana Jalaluddin Rumi