Introduction: The Complete Guide for English Readers

There are rare figures in human history whose wisdom refuses to stay within the boundaries of the religion they were born into. Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar is one of them. A Muslim Sufi saint of the Chishti Order, born in 12th-century Punjab, his words are today recited in Sikh Gurdwaras across the United States, studied in university classrooms, and cherished by millions of devotees who have never read a single line of classical Persian poetry.

His verses — preserved as Salok Sheikh Farid Ji in the Guru Granth Sahib — represent one of the most remarkable acts of interfaith spiritual recognition in the entire history of world religion. If you’ve ever wondered who Baba Farid actually was, what his saloks mean, or why a Sufi mystic’s poetry sits at the heart of Sikh scripture, this guide answers every question — clearly, completely, and in plain English.

Who Was Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar?

Baba Farid, whose full name was Sheikh Fariduddin Masood Ganj-e-Shakar, was born in 1173 CE near Multan, in the region that is today Punjab, Pakistan. He passed away in 1266 CE in Pakpattan — then known as Ajodhan — leaving behind a spiritual legacy that has outlasted empires.

The title Ganj-e-Shakar translates from Persian as “Treasure of Sugar” — a name tied to both the extraordinary sweetness of his spiritual teachings and a legendary account in which, during a prolonged fast, his mouth was found filled with sugar. Whether one reads this literally or symbolically, the title stuck for good reason. His words carry that same quality: dense with meaning, sweet with compassion, and nourishing to the soul.

He was a devoted disciple of Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki in Delhi, who was himself a successor of Moinuddin Chishti of Ajmer — the founder of the Chishti Sufi lineage in the Indian subcontinent. Through this chain, Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar became one of the most influential figures in South Asian spiritual history.

A Life Built on Radical Devotion

Baba Farid was not a comfortable mystic. His spiritual practices were intense and uncompromising. He performed extended chilla (spiritual retreats), including the demanding chilla-e-ma’koos — hanging upside down in a well for forty days of meditation. He refused gifts from rulers, lived in near-total simplicity, and fed the poor from whatever little his community could gather.

His mother, Bibi Mariam, shaped his earliest spiritual instincts. According to widely recorded tradition, she placed sugar beneath his prayer mat to encourage young Farid to pray — teaching him that devotion carries its own sweetness. He never forgot that lesson. It became the entire philosophy of his life.

What Is Salok Sheikh Farid Ji?

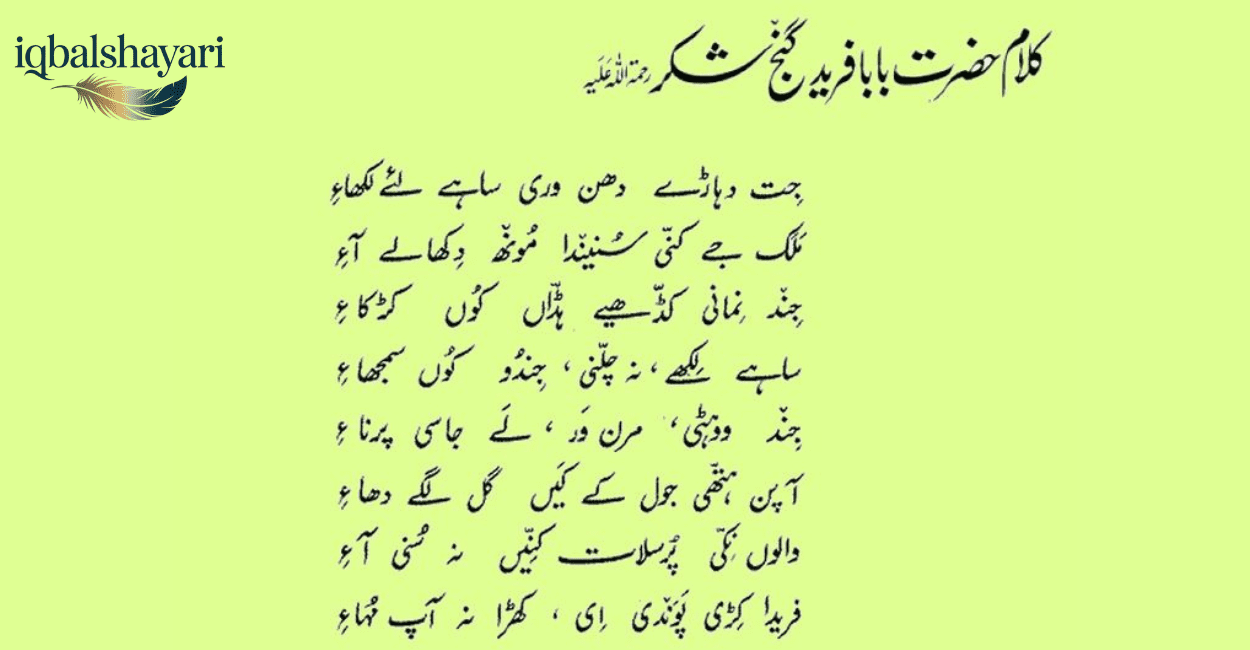

Salok Sheikh Farid Ji is a collection of 130 spiritual couplets (saloks) attributed to Baba Farid, found in the Guru Granth Sahib beginning at Ang (page) 1377. These verses are written in medieval Punjabi and Multani (Lahnda dialect) — making them the oldest surviving body of literary Punjabi in existence.

In other words, Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar is not only a Sufi saint. He is widely recognized as the first major poet of the Punjabi language — a fact that gives his inclusion in Guru Granth Sahib both spiritual and cultural significance that extends far beyond any single religious tradition.

Where Are the Saloks Found?

| Feature | Details |

| Location in Guru Granth Sahib | Ang 1377–1384 |

| Number of Saloks | 130 |

| Language | Medieval Punjabi / Multani (Lahnda) |

| Script in GGS | Gurmukhi |

| Section | Bhagat Bani (Saints’ Compositions) |

| Poetic Form | Salok / Doha (couplet) |

The saloks use the poetic convention of takhallus — a Sufi tradition of addressing oneself by name within the verse. This is why many Salok Sheikh Farid Ji begin with the word “Farida” (ਫਰੀਦਾ) — Baba Farid speaking directly to his own soul, urging it to wake up.

Why Is a Muslim Saint’s Poetry in Sikh Scripture?

This is the question most English-speaking readers ask first — and it deserves a direct, honest answer.

When Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the fifth Sikh Guru, compiled the Adi Granth in 1604 CE (later known as Guru Granth Sahib), he made a deliberate and historic decision. He included the compositions of 15 Bhagats — saints from Hindu, Muslim, and lower-caste backgrounds — alongside the words of the Sikh Gurus themselves.

The principle behind this decision is foundational to Sikh theology: truth belongs to no single religion. A soul that has genuinely realized God speaks with divine authority regardless of which tradition they were born into. Bhagat Farid Ji, as he is respectfully called in the Sikh tradition, had clearly achieved that realization. His verses aligned deeply with Sikh teachings on haumai (ego), seva (service), impermanence, and the soul’s journey toward the Divine.

Did Guru Nanak Actually Meet Baba Farid?

This is one of the most commonly misunderstood points — and getting it right matters.

Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar died in 1266 CE. Guru Nanak Dev Ji was born in 1469 CE — more than 200 years later. They never met in person. What Guru Nanak did do was visit Pakpattan Sharif, where he met Sheikh Ibrahim — the custodian of Baba Farid’s spiritual seat, sometimes called Farid II or Shaikh Braham in Sikh historical texts. During this meeting, the spiritual dialogue and exchange of Farid’s compositions are believed to have occurred.

This distinction matters because it demonstrates just how seriously the Sikh Gurus approached authenticity — they preserved and honored Baba Farid’s words even through generations of successors.

The Core Teachings of Salok Sheikh Farid Ji

The shaloks of Baba Farid are not gentle reassurances. They are urgent, sometimes stark, and always deeply human. Reading them in English, even across seven centuries and two languages, they land with remarkable force.

1. Mortality as a Teacher

More than any other theme, Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar returns to death — not as a morbid obsession but as the most reliable spiritual teacher available to every human being. His message is consistent: the body is temporary, life is brief, and every moment spent in ego or distraction is a moment lost.

One of his most quoted saloks uses the image of a bride whose wedding day also marks the arrival of death as an uninvited guest — present at every celebration, patient, certain. It’s a metaphor that has never lost its power.

2. Ego Dissolution and Humility

The Sufi concept of fana — the annihilation of the ego in God — runs through every verse. Baba Farid describes the human body as dust, the soul as a traveler at a temporary inn, and the ego as the primary barrier between the seeker and the Beloved (God). This maps precisely onto the Sikh concept of haumai as the root cause of spiritual separation.

3. Non-Retaliation and Radical Compassion

One of the most striking saloks of Sheikh Farid Ji instructs the reader that when someone strikes you with their fists, do not strike back. Instead, kiss the feet of that person and return to your own home — meaning, return to your inner sanctuary of God-consciousness. This teaching, from a 13th-century Sufi poet, reads like an instruction manual for the hardest moments of modern life.

4. Divine Love (Ishq)

The Chishti Sufi tradition places love at the center of all spiritual practice. For Baba Farid, God is the Beloved and the human soul is the lover — perpetually aching, perpetually seeking, perpetually distracted by the world. His saloks frame the spiritual path as a love story, not a transaction. You don’t earn God’s presence through ritual compliance. You surrender to it.

5. Nature as Mirror

Baba Farid uses birds, rivers, trees, seasons, and soil with extraordinary precision. A bird leaving its nest, a forest fire reducing everything to ash, bare bones bleached by the sun — his nature imagery is visceral and immediate. It has the quality of someone who spent decades in deep wilderness meditation and came back with what he saw.

Key Saloks Explained

Salok 23 — On Non-Retaliation

“Farida, those who strike you with their fists — do not strike them back. Kiss the feet of such people and return to your own home.”

This verse challenges every instinct of the ego. “Your own home” in Baba Farid’s language means the interior sanctuary of the soul — the place where God dwells undisturbed. Retaliation pulls you away from that home. Forgiveness brings you back.

Salok 79 — On the Rarity of True Seekers

“Farid says — the path of true renunciation is difficult. Walking the dervish’s way is hard. Only a rare few are accepted in the True Court of God.”

Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar never romanticized the spiritual path. He presented it as genuinely demanding — which is precisely what makes his credibility so durable. He earned his authority through practice, not proclamation.

Salok 4 — On the Hard Bread of the Spiritual Life

In this salok, Baba Farid compares the path of renunciation to eating bread made of wood — dry, hard, joyless to the ordinary senses. Yet he advocates for it without hesitation, because the alternative — a life built on ego and appetite — leads nowhere worth going.

Baba Farid’s Legacy: From Pakpattan to American Gurdwaras

After Baba Farid’s death in 1266, his dargah (shrine) at Pakpattan Sharif, Punjab, Pakistan became one of the most visited Sufi sites in South Asia. His most celebrated disciple, Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi, went on to shape the spiritual culture of the entire Mughal-era subcontinent. Through Nizamuddin, the Chishti Sufi Order extended its reach across generations, eventually influencing figures like Amir Khusrau — one of the greatest poets in South Asian history.

The Bahishti Darwaza (Door of Paradise) at Pakpattan — a sacred gate opened only during the annual Urs (death anniversary) on the 5th of Muharram — draws hundreds of thousands of pilgrims each year from Pakistan, India, and the global South Asian diaspora, including visitors from the United States.

For the Punjabi Diaspora in the USA

Across Sikh communities in Yuba City, Fresno, Stockton, New York, Chicago, Michigan, and Houston, the Salok Sheikh Farid Ji is not a historical relic. It is recited, taught, and contemplated as living scripture. Second-generation Punjabi Americans increasingly seek English-language resources to understand these verses — their linguistic heritage and their spiritual depth — without requiring fluency in classical Punjabi.

If you’re looking to engage with these teachings in the USA, several resources are immediately accessible:

- SikhNet.com — audio recitations with translations

- SearchGurbani.com — full verse-by-verse scripture database

- iGurbani app — available on US App Store and Google Play

- Gurbani.org — free online access with transliterations

- Bhai Vir Singh’s steek (commentary) — available in PDF form through various Sikh digital libraries

Many Gurdwaras in high-density Punjabi communities offer Bhagat Bani study programs and Gurbani classes where Salok Sheikh Farid Ji is taught with English explanations. Searching “Gurbani classes near me” or “Bhagat Bani study group [your city]” is a good starting point.

Common Misconceptions Corrected

“Baba Farid was a Sikh saint.” He was a Muslim Sufi master. His inclusion in Guru Granth Sahib reflects Sikhism’s recognition of universal spiritual truth — not a change in his religious identity.

“All 130 saloks were written by Baba Farid.” Some saloks in the Salok Sheikh Farid Ji section are compositions by Sikh Gurus, placed as responses or expansions of Farid’s themes. Scholars and Sikh theological tradition distinguish them clearly.

“His poetry is only about sadness and death.” The melancholy in his verses is the vehicle, not the destination. The underlying intention is joy — the joy of awakening, of divine love, of finally coming home to God.

7 Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Who was Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar?

Baba Farid (1173–1266 CE) was a revered Muslim Sufi saint of the Chishti Order, born near Multan in present-day Pakistan. His poetry is preserved in the Sikh scripture Guru Granth Sahib as Salok Sheikh Farid Ji, making him one of the most cross-tradition figures in South Asian spiritual history.

Q2: What does Ganj-e-Shakar mean?

It translates from Persian as “Treasure of Sugar.” The title refers to the sweetness of his spiritual teachings and is connected to a legendary account in which his fasting mouth was miraculously found full of sugar — symbolizing divine sustenance and grace.

Q3: How many saloks of Baba Farid are in Guru Granth Sahib?

There are 130 saloks associated with Sheikh Farid Ji in Guru Granth Sahib, found at Ang 1377–1384. Some within this collection are compositions of the Sikh Gurus written in response to or dialogue with Farid’s themes.

Q4: Did Guru Nanak Dev Ji meet Baba Farid in person?

No. Baba Farid died in 1266 CE, over 200 years before Guru Nanak’s birth in 1469 CE. Guru Nanak met Sheikh Ibrahim — the custodian of Baba Farid’s spiritual seat in Pakpattan — not Baba Farid himself.

Q5: Why is a Muslim saint’s poetry included in Guru Granth Sahib?

The Sikh Gurus recognized that divine truth transcends religious identity. Guru Arjan Dev Ji included compositions of 15 Bhagats from various traditions to demonstrate that God’s voice speaks through all sincere seekers. Baba Farid’s teachings on ego, humility, and divine love aligned deeply with Sikh theology.

Q6: What language are the Salok Sheikh Farid Ji written in?

They are written in medieval Punjabi and Multani (Lahnda dialect) — the oldest surviving literary form of the Punjabi language. In Guru Granth Sahib, they are transcribed in Gurmukhi script.

Q7: Where can I find Salok Sheikh Farid Ji translations in English?

Reliable English translations are available on SikhNet.com, SearchGurbani.com, and Gurbani.org. The iGurbani app (available on US App Store) also provides transliterations and translations. Bhai Vir Singh’s steek remains one of the most respected traditional commentaries.

Conclusion

Baba Farid Ganj-e-Shakar lived in the 13th century, wrote in a language that barely exists anymore, and practiced a form of Sufi Islam that most people in the modern world have never encountered. And yet his words — preserved as Salok Sheikh Farid Ji in the Guru Granth Sahib — feel like they were written this morning, for exactly the life you are living right now.

That is the mark of genuine spiritual authority. It doesn’t age. It doesn’t need a marketing campaign. It simply waits, patient as death itself, for the reader who is ready to hear it.

If you are part of the Punjabi diaspora in the USA, or a student of Sufi poetry, or simply someone who stumbled onto these verses and felt something shift — you are in good company. Across seven centuries, across religions, across continents, the “Treasure of Sugar” keeps offering what he always offered: a clear mirror, a hard truth, and underneath both, something unmistakably sweet.

Start at Ang 1377. Read slowly. Come back tomorrow and read again.