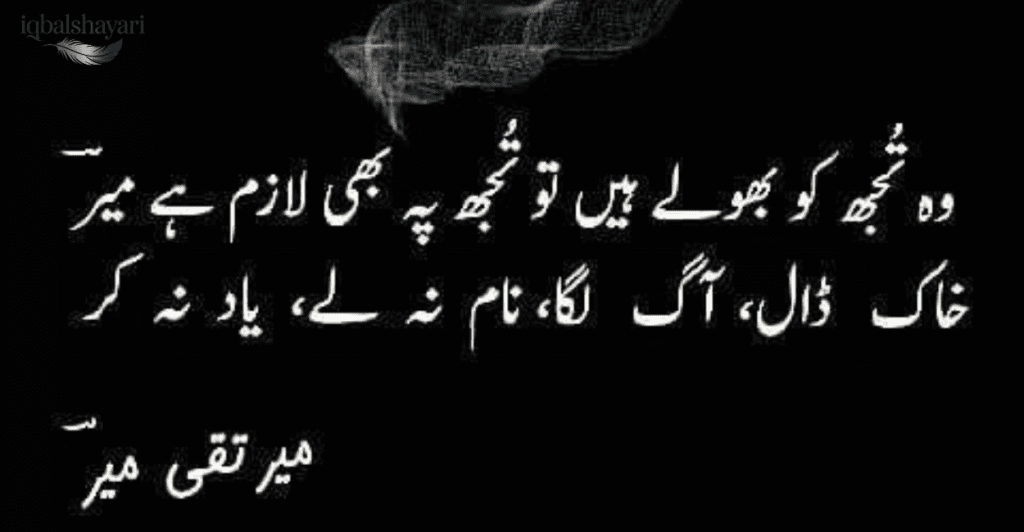

Mir Taqi Mir: The Life and Legacy of Urdu Poetry’s Greatest Master

The story of Mir Taqi Mir begins not with triumph, but with loss—a theme that would define both his life and his immortal poetry. Born in 1723 in Agra during the twilight of the Mughal Empire, Mir would witness the destruction of Delhi, experience profound personal tragedies, and yet transform suffering into some of the most emotionally authentic verses the Urdu language has ever known.

Mir Taqi Mir’s biography is inseparable from 18th-century India’s turbulent history. While most poets of his era enjoyed stable court patronage, Mir’s journey took him from the ruins of Delhi to the opulent courts of Lucknow, producing approximately 13,000 verses across six divans (poetry collections) that earned him the supreme title “Khuda-e-Sukhan”—the God of Poetry.

Early Life: Tragedy Shapes a Poet

Mir’s early life was marked by devastation that would forge his melancholic poetic voice. His father, Mir Abdullah, was a Sufi mystic and poet who provided his son’s initial education in Persian and Urdu poetry. The family traced their ancestral lineage to Hijaz in Arabia, claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammad’s family—hence the honorific “Mir,” meaning prince or leader.

Tragedy struck when Mir was just eleven years old. His father’s death left the young boy vulnerable to his step-mother’s hostility, eventually forcing him to leave home. Shortly after, his brother died, compounding his sense of abandonment and loss. These childhood experiences with death, betrayal, and displacement became the emotional foundation for poetry that would resonate across centuries.

Despite these hardships, Mir received comprehensive literary training. After his father’s death, he sought guidance from established poets including Syed Amanullah Khan (pen name: Saukhte) in Agra. This traditional ustad-shagird (master-disciple) system shaped his understanding of the ghazal form and Persian literary traditions.

The Delhi Years: Witnessing Civilization’s Collapse

In his early twenties, Mir migrated to Delhi, then known as Shahjahanabad—the magnificent Mughal capital and epicenter of Urdu literary culture. Here, he entered the vibrant world of mushairas (poetry gatherings), where poets competed for recognition and patronage from nobles.

Delhi in the 1740s was a city of contradictions. While still the Mughal capital under Muhammad Shah, political instability was growing. Mir initially struggled financially, attending public poetry symposia and seeking sporadic patronage from various nobles including Nawab Asad Khan.

The defining trauma of Mir’s life—and indeed of Delhi itself—came in 1739 when Persian emperor Nadir Shah invaded the city. The massacre of approximately 20,000-30,000 residents, the looting of treasures including the Peacock Throne, and the systematic destruction of cultural institutions devastated both the physical city and its civilizational confidence.

Mir documented this catastrophe in his autobiography Zikr-e-Mir and throughout his poetry. The ruins of Delhi became a recurring metaphor in his work—virane (ruins) symbolizing not just destroyed buildings but shattered lives and a collapsed world order. Further invasions by Ahmad Shah Abdali between 1748-1761 compounded Delhi’s decline, transforming the once-glorious capital into a shadow of its former self.

Poetic Philosophy: The Art of Beautiful Suffering

What distinguished Mir from other Urdu poets was his revolutionary approach to language and emotion. While contemporary poets favored ornate Persian vocabulary and complex metaphors, Mir perfected what literary critics call sahl-e-mumtana—poetry that appears deceptively simple yet proves impossible for others to replicate.

His verses used everyday Urdu words that even children could understand, yet contained layers of meaning that scholars continue unpacking centuries later. This accessibility combined with profound depth became his signature achievement.

Mir’s poetic philosophy centered on several interconnected concepts. Ishq (love) wasn’t merely romantic attraction but a transformative force leading to spiritual refinement through suffering. Gham (sorrow) represented the authentic human condition—not something to avoid but to embrace as the path to truth. The beloved’s cruelty and indifference weren’t flaws but necessary tests of the lover’s devotion.

This worldview drew heavily from Islamic mystical traditions, particularly Sufism. Concepts like fana (annihilation of the ego) and the wine-house as a metaphor for divine intoxication permeate his work. Yet Mir’s genius lay in making these mystical concepts feel intensely personal and emotionally immediate.

The Six Divans: A Monumental Literary Legacy

Mir’s primary legacy consists of six collected volumes of Urdu ghazals compiled over his lifetime. The first diwan appeared around 1751, with subsequent collections following in 1757, 1765, 1773, and two more in the 1780s-1790s. Each contained approximately 350-400 ghazals, totaling roughly 13,000 verses—an extraordinary output maintained at consistently high quality.

Beyond Urdu poetry, Mir also composed a Persian diwan and several prose works. His autobiography Zikr-e-Mir (Memoirs of Mir), written in Persian, provides invaluable insights into 18th-century Delhi’s literary culture and his personal experiences. Nikat-ush-Shu’ara (Poets’ Subtleties) served as a biographical dictionary of Urdu and Persian poets, containing his critical assessments of contemporaries and predecessors.

The ghazal form that Mir mastered consists of independent couplets (shers) linked by rhyme scheme and meter but complete in themselves. Each couplet must stand alone as a complete thought—a demanding constraint that Mir transformed into opportunity for concentrated emotional expression.

Migration to Lucknow: Exile and Nostalgia

By the 1780s, Delhi’s collapse was complete. The patronage system had disintegrated, violence was endemic, and the cultural infrastructure lay in ruins. Mir, now in his sixties, made the painful decision to migrate to Lucknow, the capital of Awadh under Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula.

Lucknow had emerged as a new cultural center, attracting poets, artists, and intellectuals fleeing Delhi’s devastation. Asaf-ud-Daula offered generous patronage, and Mir received a monthly stipend that provided material security for his final decades.

Yet Mir never reconciled with Lucknow. Despite comfort and respect, his poetry from this period overflows with nostalgia for Delhi. He criticized Lucknow’s literary culture as frivolous compared to Delhi’s lost sophistication. The displacement he felt—comfortable yet homeless, honored yet alien—adds poignant complexity to his later work.

His verses from this period lament Delhi’s ruins with such intensity that they transcend personal loss to become meditations on impermanence, the price of history’s violence, and the impossibility of return. Mir died in Lucknow in 1810 at approximately 87 years old, buried in a city that never quite became home.

Mir’s Unique Style: Language as Emotional Truth

What makes Mir’s poetry immediately recognizable is its emotional directness. Where other poets constructed elaborate conceits, Mir spoke straight from wounded experience. His beloved’s cruelty feels real because it draws from actual abandonment. His tears and sighs aren’t poetic conventions but authentic expressions of grief.

The language Mir used was revolutionary for its time. He elevated colloquial Urdu—the everyday speech of Delhi’s streets—into high literary art. While Persian remained the language of prestige and earlier Urdu poets heavily Persianized their vocabulary, Mir proved that simple Urdu words could convey the most profound emotions and complex ideas.

His technical mastery of meter (bahr) allowed him to work within strict formal constraints while maintaining conversational naturalness. The rhyme scheme’s demands never made his verses feel forced or artificial. This seamless integration of form and feeling exemplifies his artistry.

Contemporary Rivalries: Mir Among the Masters

Mir existed within a vibrant literary community that included several other exceptional poets. His most famous rivalry was with Mirza Muhammad Rafi Sauda, master of satirical poetry. While occasionally contentious, both acknowledged each other’s genius in their respective domains—Mir in ghazal, Sauda in satire.

Khwaja Mir Dard, a Sufi poet and near-contemporary, emphasized mystical themes with different stylistic choices. The comparison between Mir and Dard highlights how different temperaments could excel within the same tradition. Mir Hasan, another Delhi poet, contributed to the era’s literary richness.

These poets competed at mushairas, where audiences judged recitations and poetic challenges tested wit and skill. This competitive environment pushed poets toward excellence while establishing standards that shaped Urdu poetry’s evolution.

The Mir vs. Ghalib Debate

Perhaps no question in Urdu literary history has generated more discussion than comparing Mir with Mirza Ghalib. Ghalib (1797-1869) represents the next generation’s peak achievement, and literary enthusiasts have debated their relative merits for over a century.

The distinction often comes down to heart versus mind. Mir’s poetry flows from emotional truth—direct, vulnerable, accessible. Ghalib’s verses engage intellectual complexity—paradoxical, philosophically dense, requiring contemplation. Mir wrote in simpler Urdu; Ghalib employed heavier Persian influence.

Critical consensus often gives Mir the edge in pure ghazal form for emotional authenticity and linguistic purity, while acknowledging Ghalib’s greater range across genres and philosophical depth. Both are supreme masters; the preference depends partly on what readers seek from poetry—immediate emotional connection or intellectual engagement.

Themes That Define Mir’s Poetry

Mir’s thematic preoccupations create a recognizable universe across his 13,000 verses. Unrequited love dominates—not as abstract concept but as lived experience of longing, rejection, and patient devotion. The beloved’s indifference and cruelty aren’t obstacles to love but its essential nature.

Sorrow (gham) pervades his work not as depression but as the authentic response to existence. Mir finds beauty in tears, dignity in suffering, truth in melancholy. This isn’t nihilism but a profound acceptance that acknowledges life’s pain while finding meaning within it.

The ruins metaphor operates on multiple levels. Delhi’s physical destruction mirrors personal devastation mirrors spiritual desolation. Virane (ruins) represent what’s lost but also what remains—memory, meaning, the persistence of beauty amid destruction.

Mystical themes drawn from Sufi tradition provide theological framework. Divine love expressed through earthly beloved, wine as metaphor for spiritual intoxication, annihilation of ego as path to union—these concepts give Mir’s romanticism spiritual depth beyond mere heartbreak.

Legacy and Influence on Urdu Literature

Mir achieved recognition during his lifetime—unusual for artists. His contemporaries acknowledged him as the supreme master, and this reputation has only strengthened over two centuries. The honorific “Khuda-e-Sukhan” (God of Poetry) reflects both his technical mastery and his profound influence on all subsequent Urdu poetry.

Later poets including Ghalib referenced Mir as the standard. The 19th-century romantics Momin Khan Momin and others carried forward aspects of Mir’s tradition. Even modernist poets of the 20th century—Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Ahmad Faraz—acknowledge his foundational importance.

In American academia, Mir’s work features in South Asian studies programs at major universities including Columbia, University of Chicago, UC Berkeley, and Yale. His poetry provides essential material for understanding Mughal cultural history, Urdu linguistic development, and the intersection of personal and historical trauma.

For South Asian diaspora communities in the United States—particularly in New York, Chicago, Houston, and the San Francisco Bay Area—Mir’s poetry maintains cultural relevance. Mushairas (poetry recitations) in these cities regularly feature his ghazals, and cultural organizations use his work to connect younger generations with linguistic heritage.

Finding Mir’s Poetry Today

English-speaking readers can access Mir’s work through several translations. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s scholarly editions provide both translation and extensive commentary. Various anthologies include selections alongside other Urdu masters. Online platforms like Rekhta.org offer free access to Mir’s complete divans with transliteration and English translations.

Physical books are available through major retailers, with paperback translations typically priced $15-35 and academic editions $40-75. University libraries with South Asian collections—particularly at institutions with Urdu programs—maintain comprehensive holdings.

For those interested in deeper engagement, universities across the United States offer Urdu language and literature courses. Community centers in cities with significant South Asian populations provide Urdu classes where Mir’s poetry often features prominently.

Why Mir Matters to Modern Readers

Mir’s themes transcend their 18th-century context to speak to universal human experiences. Loss, displacement, unrequited longing, finding meaning amid suffering—these resonate regardless of cultural background. For immigrant communities, his experience of forced migration and nostalgia for lost homeland carries particular poignancy.

His technical achievement—proving that vernacular language could produce great art—parallels modern movements valuing indigenous voices over colonial languages. His emotional honesty challenges contemporary cynicism about authentic feeling.

For anyone interested in world literature beyond the Western canon, Mir represents South Asian literary tradition at its finest. His work demonstrates that every culture has produced artists whose achievements merit global recognition.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Mir Taqi Mir and why is he famous?

Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810) was an 18th-century Urdu poet from Delhi, renowned as the greatest master of Urdu ghazal poetry. He’s famous for transforming personal suffering and historical trauma into emotionally authentic verses using simple yet profound language. His six divans containing approximately 13,000 verses established him as “Khuda-e-Sukhan” (God of Poetry), and his influence on all subsequent Urdu literature remains unmatched.

When and where was Mir Taqi Mir born?

Mir Taqi Mir was born in 1723 in Agra, India, during the Mughal Empire period. His family, originally from Hijaz in Arabia, had settled in India during earlier Mughal times. His father Mir Abdullah was a Sufi mystic and poet who provided his initial literary education before dying when Mir was approximately eleven years old.

How many books did Mir Taqi Mir write?

Mir compiled six divans (collections) of Urdu ghazals containing approximately 13,000 total verses, plus one Persian diwan. His major prose works include Zikr-e-Mir (his autobiography in Persian), Nikat-ush-Shu’ara (a biographical dictionary of poets), and Faisla-e-Kada-o-Kharab (allegorical prose work). The six Urdu divans represent his primary literary legacy and were compiled progressively from around 1751 through the 1790s.

What is the difference between Mir and Ghalib?

Mir (1723-1810) used simpler, more Urdu-based language with direct emotional expression focusing on the heart, while Ghalib (1797-1869) employed complex, Persian-influenced language with intellectual depth emphasizing the mind. Mir perfected sahl-e-mumtana (seemingly simple yet profound) style, whereas Ghalib created dense, multi-layered meanings. Critical consensus often gives Mir the edge in pure ghazal form for emotional authenticity, while acknowledging Ghalib’s greater philosophical range.

Why is Mir called Khuda-e-Sukhan (God of Poetry)?

Mir earned this supreme honorific for several reasons: his unmatched emotional authenticity in expressing love and suffering, his perfection of the seemingly simple yet impossible-to-imitate style, his massive output of 13,000 high-quality verses, his technical mastery of ghazal form, and his elevation of colloquial Urdu to high literary art. Even contemporary and later poets, including Ghalib, acknowledged Mir’s supremacy in certain dimensions of ghazal composition.

What were the main themes in Mir’s poetry?

Mir’s primary themes include unrequited love and longing, suffering and melancholy as the authentic human condition, mystical concepts of divine love and self-annihilation (fana), the decline of Delhi and Mughal civilization, personal tragedies and losses, the beloved’s cruelty and the lover’s patient devotion, and existential reflections on fate, death, and transience. Ruins (virane) serve as his dominant metaphor for both personal and civilizational collapse.

How did historical events affect Mir’s poetry?

Nadir Shah’s devastating 1739 invasion of Delhi, which killed thousands and destroyed the city’s cultural infrastructure, profoundly shaped Mir’s poetic vision of loss and ruin. Repeated Afghan invasions (1748-1761) deepened his melancholic worldview. The Mughal Empire’s decline mirrors his themes of decay and transience. His forced migration from Delhi to Lucknow in 1782 intensified his nostalgia and sense of displacement. Personal losses—father, brother, friends—merged with civilizational collapse in his work.

Where can I find Mir Taqi Mir’s poetry in English?

English translations are available through scholarly editions by translators like Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, various anthologies of Urdu poetry, and online platforms like Rekhta.org which offers free access to Mir’s complete divans with transliteration and English translations. Physical books can be purchased through major retailers ($15-35 for paperbacks, $40-75 for academic editions). University libraries at institutions with South Asian studies programs—particularly Columbia, University of Chicago, UC Berkeley, and Yale—maintain comprehensive collections.

Conclusion

Mir Taqi Mir’s biography tells the story of genius forged in catastrophe. From childhood tragedies through Delhi’s destruction to exile in Lucknow, he transformed personal and historical suffering into poetry that continues moving readers nearly two centuries after his death. His 13,000 verses across six divans didn’t just master the ghazal form—they redefined what Urdu poetry could express and how it could speak.

His achievement extended beyond individual brilliance to shape an entire literary tradition. By proving that simple, everyday Urdu could convey the most profound emotions and complex ideas, Mir elevated his mother tongue to literary respectability. Every Urdu poet who followed worked in the tradition he established.

For modern readers—whether South Asian diaspora maintaining cultural connections, students exploring world literature, or anyone seeking poetry that speaks truth about love, loss, and the human condition—Mir’s work remains vitally relevant. His themes transcend their 18th-century context to address universal experiences of longing, displacement, and finding meaning amid suffering.

The ruins of Delhi that haunt his verses might be gone, but the emotional landscapes he mapped remain eternally present. In grief’s geography and love’s impossible terrain, Mir remains the supreme guide—the God of Poetry whose words continue illuminating the beautiful, terrible truth of being human.