Introduction: Who Redefined American Modernism

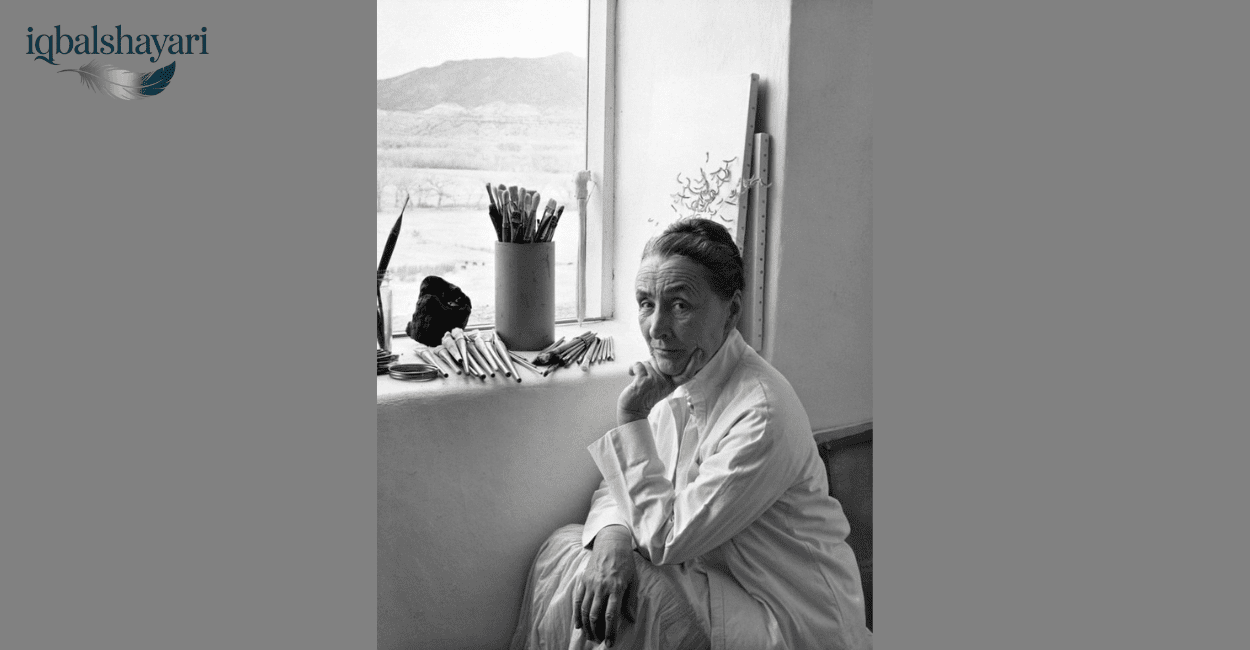

When Georgia O’Keeffe looked at a flower, she didn’t see what most people saw. She saw architecture, emotion, and an entire universe compressed into petals and stamens. This unique vision transformed her into one of America’s most celebrated painters and earned her the title “Mother of American Modernism.”

Born in 1887 on a Wisconsin dairy farm, O’Keeffe defied every expectation placed on women of her era. She didn’t just become an artist—she became a force that reshaped how Americans understood their own landscape, culture, and artistic potential.

Her journey from rural farmland to the pinnacle of the art world spans seven decades of relentless creativity. Along the way, she created paintings so iconic that even people who’ve never set foot in a museum recognize her magnified irises and sun-bleached skulls against vast New Mexico skies.

Who Was Georgia O’Keeffe?

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe lived from November 15, 1887, to March 6, 1986, reaching the remarkable age of 98. She spent over 70 years creating art that challenged conventions and expanded what American painting could be.

Unlike European artists who dominated the early 20th century art scene, O’Keeffe looked inward to American subjects. She found profound beauty in places others overlooked—a single flower, a weathered animal bone, the endless desert stretching toward distant mesas.

Her approach was revolutionary. While male contemporaries focused on industrial scenes and urban chaos, O’Keeffe magnified natural forms to monumental scale. A four-foot canvas might contain nothing but the intimate folds of a single iris petal, forcing viewers to slow down and truly see.

She became the first female artist to receive a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1946, cementing her position as a major American painter during her lifetime—not just in retrospect.

The Path to Artistic Independence

O’Keeffe’s determination to become an artist emerged early. At age 10, she announced her intention to her childhood friend, an unusual ambition for a farm girl in 1890s Wisconsin.

Her formal training began at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1905, where she learned traditional academic painting. She excelled at precise draftsmanship, winning awards for her technical skill. But something felt incomplete.

At the Art Students League in New York, she studied under William Merritt Chase, mastering oil painting techniques. Yet the European-influenced curriculum left her searching for her own voice.

The breakthrough came through Arthur Wesley Dow, whose teaching philosophy emphasized filling space beautifully rather than copying reality. Dow introduced O’Keeffe to Japanese aesthetics and the idea that composition and design mattered more than realistic representation.

In 1915, while teaching art in South Carolina, O’Keeffe created a series of abstract charcoal drawings unlike anything she’d done before. These flowing, organic forms represented her first mature artistic statement—work that was undeniably hers alone.

When these drawings reached Alfred Stieglitz, the famous photographer and gallery owner in New York, he exhibited them without permission. O’Keeffe was furious at first, but this bold move launched her professional career and began one of art history’s most complex partnerships.

The Signature Style That Changed Everything

O’Keeffe’s paintings are instantly recognizable because she developed techniques that were entirely her own.

Extreme magnification became her trademark. She would isolate a subject—usually something small and organic—and paint it at enormous scale. What should be a delicate three-inch flower became a commanding four-foot presence that dominated entire walls.

Her cropping technique was equally radical. She eliminated context, backgrounds, and anything extraneous. A flower might be cropped so tightly that only its central forms remained visible, creating compositions that hovered mysteriously between recognition and abstraction.

Bold, unmodulated color gave her work visceral impact. Rather than subtle gradations, she often used flat fields of saturated color. Deep purples bled into blacks. Brilliant whites glowed against soft grays. The colors felt emotional rather than naturalistic.

She simplified forms to their geometric essence. Petals became curves and arcs. Landscapes reduced to horizontal bands. This Precisionism approach created images that felt both sharply modern and timelessly elemental.

The controversial aspect of her work emerged immediately. Critics, influenced by Freudian psychology popular in the 1920s, interpreted her flower paintings as sexual imagery. O’Keeffe repeatedly rejected these readings, insisting people were simply uncomfortable with work created by a woman. She painted flowers large, she explained, because busy New Yorkers walked past beauty without noticing. She wanted to force them to take time looking.

The Most Famous Georgia O’Keeffe Paintings

“Black Iris” (1926) remains her most iconic flower work. The deep purple iris opens at monumental scale, its velvety petals creating an almost architectural space. The painting’s abstract qualities and mysterious depth make it endlessly fascinating.

“Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1” (1932) achieved a different kind of fame. In 2014, it sold at auction for $44.4 million, setting the record for the highest price ever paid for a painting by a female artist. The massive white trumpet flower seems to glow with inner light against a pale background.

“Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills” (1935) perfectly captures O’Keeffe’s New Mexico vision. A bleached ram skull floats in front of colorful desert hills, with a single white flower placed mysteriously beside it. The painting combines death and beauty, harshness and delicacy, in a way that defines the Southwestern landscape.

Her New York period produced striking urban works too. “Radiator Building—Night, New York” (1927) shows a Manhattan skyscraper at night, its windows glowing, a red neon sign visible. The painting celebrates American industrial modernity with the same intensity she brought to natural subjects.

“Sky Above Clouds IV” (1965) represents her late-period ambition. Created when she was 78 years old, this massive painting measures 8 by 24 feet. It shows rows of clouds extending to the horizon, inspired by views from airplane windows. The scale and serenity demonstrate that her creative powers remained formidable into old age.

The New Mexico Years: Finding Home in the Desert

O’Keeffe first visited New Mexico in 1929 at age 41. She stayed in Taos as the guest of arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan. The landscape immediately captivated her. She later described it as “a beautiful, untouched lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the ‘Faraway.'”

The high desert’s brilliant light, dramatic geological formations, and vast empty spaces spoke to something deep in O’Keeffe’s temperament. Unlike the crowded, competitive New York art world, New Mexico offered solitude and visual drama.

In 1940, she purchased a small house at Ghost Ranch near Abiquiú in northern New Mexico. The property provided spectacular red cliffs, endless sky, and the isolation she craved for sustained work. She spent summers there, painting the surrounding landscape obsessively.

Five years later, she bought a dilapidated adobe compound in Abiquiú village itself. She spent years renovating the thick-walled structure, creating a home that reflected her aesthetic—spare, elegant, perfectly proportioned. A door in the patio wall appeared in numerous paintings, becoming as iconic as her flowers.

After Alfred Stieglitz died in 1946, O’Keeffe moved permanently to New Mexico. She was 59 years old, and the desert became the primary source for the rest of her artistic life.

The New Mexico paintings established new visual vocabulary. Bleached animal bones collected from the desert became recurring subjects—not morbid symbols but beautiful sculptural forms that spoke to the landscape’s harsh honesty. She often painted bones against bright blue sky, creating startling juxtapositions.

The mesas, cliffs, and distinctive flat-topped Pedernal Mountain appeared repeatedly. O’Keeffe once said Pedernal was “her mountain,” claiming God told her if she painted it enough, he would give it to her.

Where to Experience Georgia O’Keeffe’s Art Today

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, holds the world’s largest collection with over 3,000 works. Located at 217 Johnson Street in downtown Santa Fe, the museum offers comprehensive survey of her entire career. Admission costs $22 for adults, with free entry for visitors under 18.

Beyond viewing paintings, the museum offers guided tours of O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú home and studio from March through November. These tours require advance reservations—often booking months ahead for summer dates. Tickets cost approximately $45-$65 per person for the one-hour tour. Visitors see the rooms where O’Keeffe lived and worked, including her bedroom, studio, garden, and the famous patio door she painted.

Ghost Ranch tours are also available through advance reservation, offering views of the landscape that inspired hundreds of paintings.

Major museums across America hold important O’Keeffe works. The Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York feature significant holdings. The Art Institute of Chicago, where she studied, maintains strong collections. The Whitney Museum, National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and Milwaukee Art Museum all display representative works from multiple periods.

Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas, owns the record-breaking “Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1” purchased in 2014.

For those planning New Mexico visits, late spring (May-June) or early fall (September-October) offer the comfortable temperatures and clear skies O’Keeffe painted. Santa Fe sits about an hour north of Albuquerque, while Abiquiú is 45 minutes north of Santa Fe.

The Alfred Stieglitz Partnership

Alfred Stieglitz, already famous as a photographer and gallery owner promoting modern art, first encountered O’Keeffe’s work in 1916. At 52, he was 23 years older than the 28-year-old artist.

He immediately recognized her talent and began exhibiting her abstract drawings at his legendary 291 Gallery. He also began photographing her extensively, ultimately creating over 300 portraits between 1917 and 1937—one of photography’s most famous portrait series.

Their relationship evolved from professional mentor-protégée to romantic partnership. Stieglitz divorced his first wife and married O’Keeffe in 1924.

The partnership proved simultaneously supportive and constraining. Stieglitz promoted O’Keeffe’s work brilliantly, organizing exhibitions, connecting her with collectors, and controlling pricing strategies. His advocacy helped establish her commercial success.

However, tensions emerged. Stieglitz encouraged critical interpretations of her flower paintings that O’Keeffe found reductive and frustrating. His Freudian-influenced framing emphasized sexuality in ways she never intended. She wanted recognition as an artist, not as a “woman artist” whose work revealed feminine psychology.

By the late 1920s, their needs diverged sharply. O’Keeffe craved New Mexico’s isolation. Stieglitz required New York’s cultural engagement. From 1929 onward, they maintained the marriage but lived separately for months each year.

When Stieglitz died in 1946, O’Keeffe spent three years settling his massive estate, distributing his art collection to museums. Then she moved permanently to New Mexico, establishing complete independence at age 59.

Breaking Barriers and Building Legacy

O’Keeffe’s success proved that female artists could achieve commercial viability and critical recognition equal to male peers. She commanded high prices throughout her career—by the 1940s, she was among the highest-paid living American artists regardless of gender.

She demonstrated that American landscapes could be legitimate subjects for serious modernist art. Before her generation, American painters largely imitated European trends and subjects. O’Keeffe helped establish that American Modernism could have its own distinctive voice.

The feminist art movement of the 1970s claimed O’Keeffe as a pioneering figure, though she resisted the label. She preferred recognition simply as an artist rather than specifically as a “woman artist.” This tension between her actual stance and her symbolic importance continues generating discussion.

Her influence extends through multiple generations. Color field painters drew inspiration from her large, simplified color areas. Photographers learned from her collaboration with Stieglitz. Environmental artists and land artists found precedent in her attentiveness to natural forms. Contemporary artists working with scale, abstraction, and female identity all reference her legacy.

O’Keeffe continued working into her 80s, only stopping when macular degeneration severely limited her vision. She painted her last unassisted oil painting in 1972 at age 85. She died in Santa Fe on March 6, 1986, at age 98.

Collecting Georgia O’Keeffe: Prints, Books, and Originals

Original O’Keeffe paintings rarely appear on the market, with most held in museum collections or private estates. When major works reach auction, prices range from $3 million to over $40 million.

Authorized reproductions and prints are available through the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum store in Santa Fe and online. Major museums holding her work also offer licensed print reproductions, typically $25-$200 depending on size and quality.

Essential books include Roxana Robinson’s definitive biography “Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life,” the comprehensive “Catalogue Raisonné” documenting all known works, and “My Faraway One: Selected Letters” revealing her relationship with Stieglitz through their own words.

Museum exhibition catalogs from major retrospectives provide scholarly analysis and high-quality reproductions of specific periods or themes in her work.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Georgia O’Keeffe most famous for?

Georgia O’Keeffe is most famous for her large-scale flower paintings that magnified botanical subjects to monumental proportions, her New Mexico desert landscapes featuring bleached animal bones and colorful mesas, and her pioneering role in American modernist art. Her distinctive style combined precise representation with abstract design principles.

Why did Georgia O’Keeffe paint flowers so large?

O’Keeffe painted flowers at extreme scale to force viewers to slow down and truly see them. She explained that busy New Yorkers rushed past small blooms without noticing their beauty. By magnifying a single iris or poppy to fill a four-foot canvas, she eliminated distractions and created immersive visual experiences that demanded attention.

Did Georgia O’Keeffe have children?

No, Georgia O’Keeffe never had children. She dedicated herself entirely to her artistic career and believed motherhood would interfere with her creative independence. Her marriage to Alfred Stieglitz produced no children, partly because he already had a daughter from his first marriage and partly by O’Keeffe’s choice to prioritize art.

Where can I see Georgia O’Keeffe paintings?

The largest collection exists at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, with over 3,000 works. Major holdings also appear at the Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum in New York, Art Institute of Chicago, National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and Whitney Museum. Most major American art museums feature at least some O’Keeffe works.

What technique did Georgia O’Keeffe use?

O’Keeffe primarily worked in oil on canvas, applying paint in smooth, even layers with minimal visible brushstrokes. She used magnification and tight cropping to eliminate context, forcing focus on essential forms. Her technique emphasized bold, unmodulated color fields and simplified shapes that reduced complex subjects to fundamental geometric elements.

How much is a Georgia O’Keeffe painting worth?

Original O’Keeffe paintings range from $3 million to over $44 million at auction. Her “Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1” sold for $44.4 million in 2014, setting the record for artwork by a female artist. Smaller works, drawings, and watercolors typically sell in the $500,000 to $5 million range when they appear on the market.

Was Georgia O’Keeffe a feminist?

O’Keeffe resisted the feminist label despite becoming a feminist icon. While she broke gender barriers and achieved success in a male-dominated art world, she preferred recognition as an artist rather than specifically as a “woman artist.” During the 1970s feminist art movement, younger artists claimed her as a pioneer, but O’Keeffe maintained her work addressed universal visual themes.

What inspired Georgia O’Keeffe’s art?

O’Keeffe drew inspiration from natural forms—flowers, bones, rocks, shells—that she collected and arranged in her studio. New Mexico’s landscape profoundly influenced her mature work, providing dramatic geological formations, brilliant light, and cultural solitude. Her teacher Arthur Wesley Dow’s philosophy of “filling space beautifully” shaped her compositional approach throughout her career.

Conclusion

Georgia O’Keeffe transformed American art by proving that regional landscapes could carry modernist power, that female artists could command respect equal to male contemporaries, and that sustained creative evolution across seven decades was achievable.

Her paintings continue resonating because they balance accessibility with complexity. Casual viewers appreciate the beauty of magnified irises while art historians analyze sophisticated handling of form, space, and color theory. Her work appears equally on museum walls and dorm room posters—testament to both visual power and cultural penetration.

For those drawn to O’Keeffe’s vision, visiting Santa Fe and experiencing the New Mexico landscape she painted offers profound connection. Walking through Abiquiú, seeing Pedernal Mountain, or standing before her massive canvases at the museum provides understanding no reproduction can match.

Her legacy extends beyond individual paintings to her example: that artistic integrity matters more than acceptance, that subjects dismissed as minor can become monumental, and that place—whether a flower, a skull, or endless desert—deserves sustained, respectful attention. In an age of distraction, Georgia O’Keeffe still teaches us how to truly see.

Read more: Andy Warhol